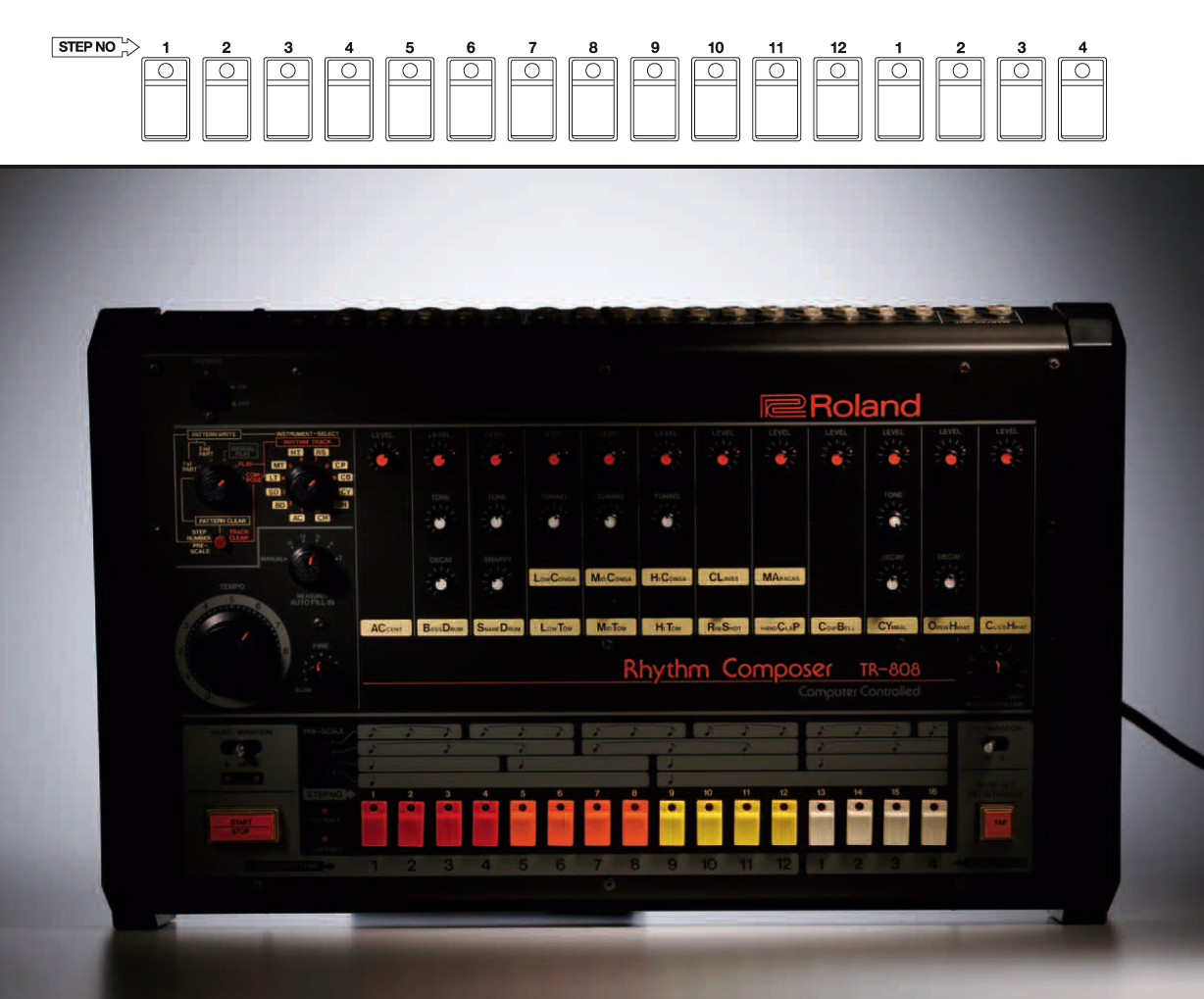

‘Joe Mansfield’s Beat Box Book’ is a beautiful collection of the best of his nearly 150 item collection of drum machines, published by his newly minted Get On Down book imprint. Joe bought his first drum machine, the Roland TR 808, in 1985 and was hooked, later going into production for rappers like Edo G and Scientifik before founding the Traffic Entertainment label which specialises in high end Hip Hop reissues.

‘Joe Mansfield’s Beat Box Book’ is a beautiful collection of the best of his nearly 150 item collection of drum machines, published by his newly minted Get On Down book imprint. Joe bought his first drum machine, the Roland TR 808, in 1985 and was hooked, later going into production for rappers like Edo G and Scientifik before founding the Traffic Entertainment label which specialises in high end Hip Hop reissues.

I’m no hardware enthusiast and have only ever owned a handful of pieces of outboard kit in my time, preferring to work ‘in the box’ so to speak, but I can appreciate the visual appeal of a lot of these beat boxes even if I could only identify a few by ear. But being that this is a book and not a record, the aesthetics of these machines is what it’s all about and I doubt that anyone could have taken more care and done as much justice to their visual appeal as this book has. The photography is perfect, lighting the subjects so as to highlight their shape, textures and features beautifully whilst never shying away from the ravages that some of them have suffered at the hands of their owners over time.

But it’s not just a photo gallery, we’re also treated to reproductions of the graphics, manuals, vintage advertising material and even some of the original boxes they would have come in in all their faded, battered and taped-up glory. Whilst the 808, 909, DMX and Linn drums will be the most familiar, some of their close relatives are also featured like the Roland TR-55, TR-330, CR-78 Rhythmatic and Linn 9000.

But it’s not just a photo gallery, we’re also treated to reproductions of the graphics, manuals, vintage advertising material and even some of the original boxes they would have come in in all their faded, battered and taped-up glory. Whilst the 808, 909, DMX and Linn drums will be the most familiar, some of their close relatives are also featured like the Roland TR-55, TR-330, CR-78 Rhythmatic and Linn 9000.

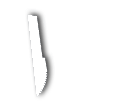

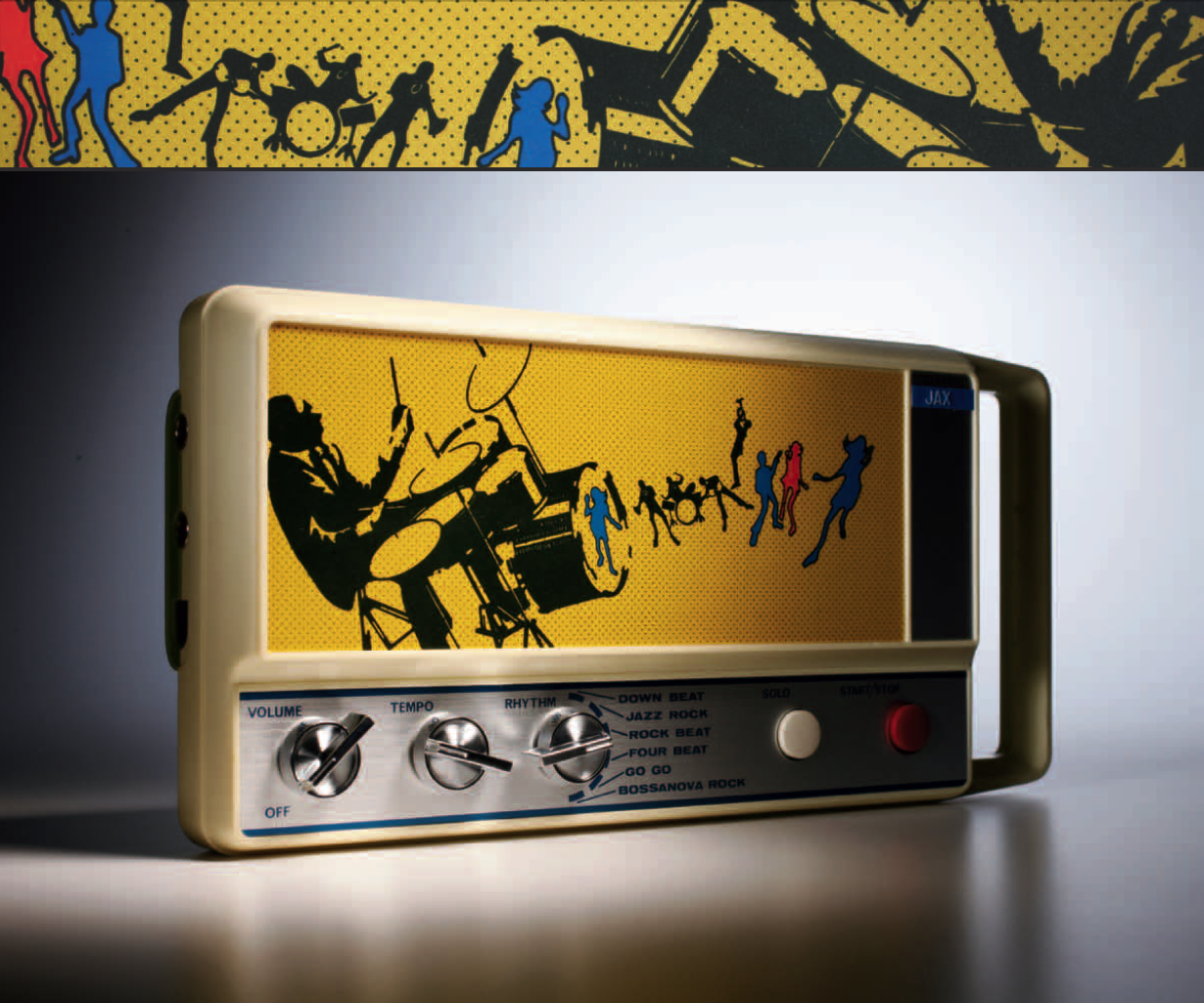

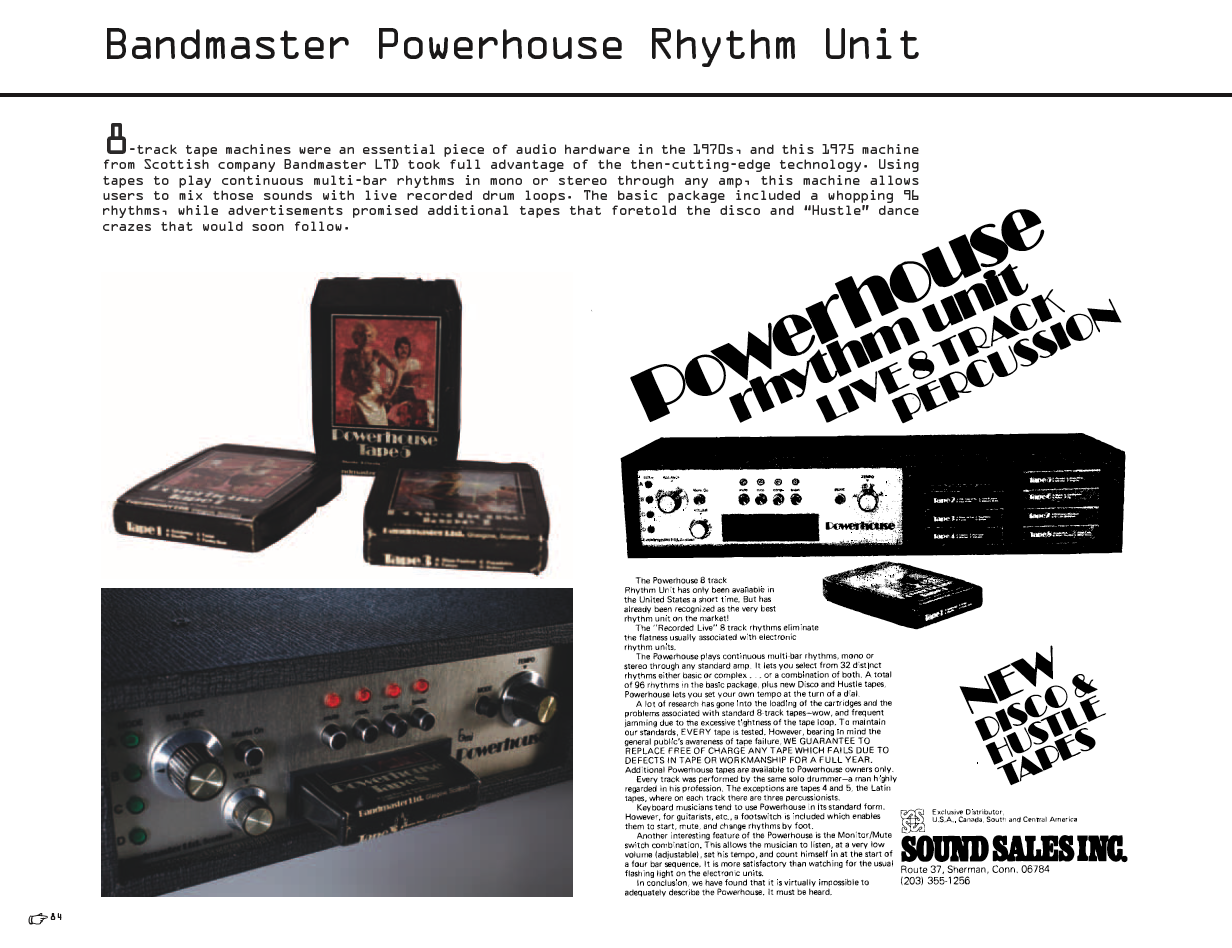

There are some real curios here too, mostly from the crossover commercial market outside of the pro studio environment. The Rhythmatic Electronic Rhythm Section, with its ‘let’s take it out for a picnic’ carry handle and funky drummer graphic over the speaker for instance. The Casio PT-7 with its dinky, detachable keyboard or the Mattel Bee Gees (yes, those Bee Gees) Rhythm Machine which Kraftwerk famously bastardised to use on tour when they played ‘Pocket Calculator’. My favourite is the Bandmaster Powerhouse Rhythm Unit, a drum machine from 1975 that also played 8-Track tapes and allowed you to mix drum loops with your albums.

There’s some gorgeous typography too in the brand logos and machine identities plus the whole book is set in the OCR-A font – not your regular choice for large blocks of text but befitting the subject matter no end.

There are a few machines that will be nearly as familiar as the Roland‘s and Oberheim‘s on display here too. Many will remember the Casio VL-Tone VL-1, a regular of high street gadget and hi-fi shops as well as toy stores, the Boss Dr. Rhythm units and the Mattel Synsonics Drums with their four pads that could be hit with sticks.

The 808, 909, DMX and Linn drums get the lion’s share of the spotlight plus there are interviews with Roger Linn, Davy DMX, Schoolly D (about the 909) but nothing for the 808, which is a shame as someone like John Robie would have been a nice addition. This is a minor quibble, probably the only one, about a book which has a visual appeal far beyond the audio hardware fetish crowd. I wonder if we’ll see book collections showcasing the interfaces of classic software in another 20 years time? I doubt they’ll have quite the same appeal as this book does.

You can read more about it here and order a copy here including the regular version or a slip cased special edition with extra 7″ and cassette.