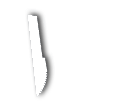

Soviet flexi discs, ‘bones’ or ‘ribs’, music pressed on old X-Rays due to lack of resources. Stephen Coates aka The Real Tuesday Weld has been collecting and exhibiting these for a while now and Strangeattractor Press are publishing a book of them this autumn. Pre-order is here and there is a limited edition with a free flexi disc which I will no doubt be featuring in the Flexibition at some point.

Next week, Tuesday 30th June, Stephen will be telling the story of the X-Ray Bootleggers at The Last Tuesday Society. More details and tickets here…

…and on Friday 3rd July Stephen and Aleks Kolkowski will be presenting a special evening at the Masonic Temple of the Andaz Hotel as part of the East End Film Festival. A new x-ray record will be cut live with a 1940s recording lathe from a live performance by Marcella Puppini of The Puppini Sisters. Go HERE for more details and tickets

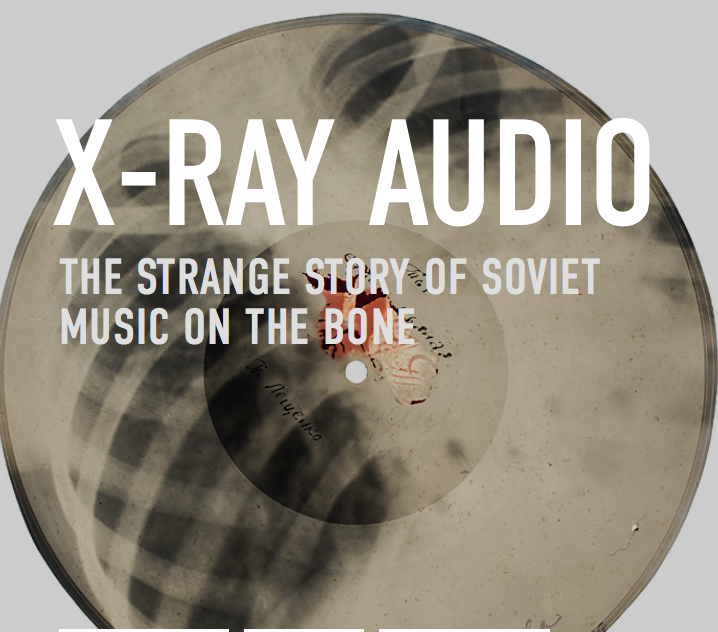

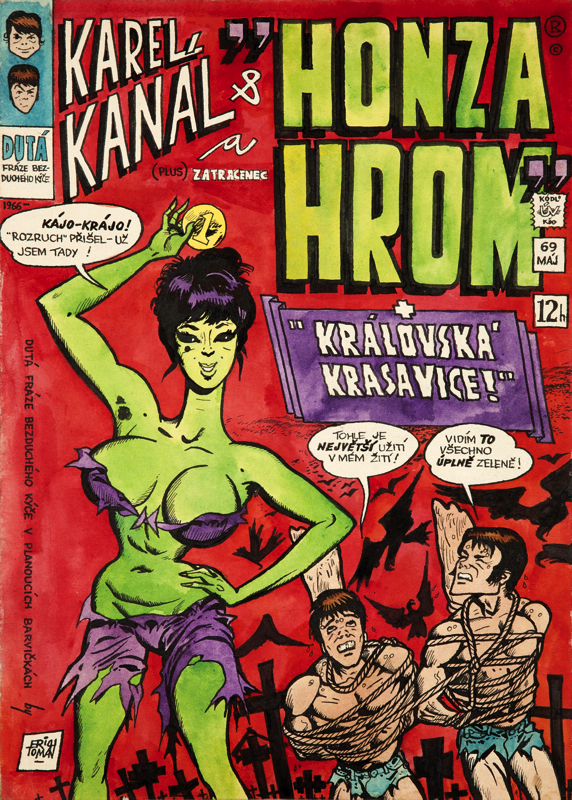

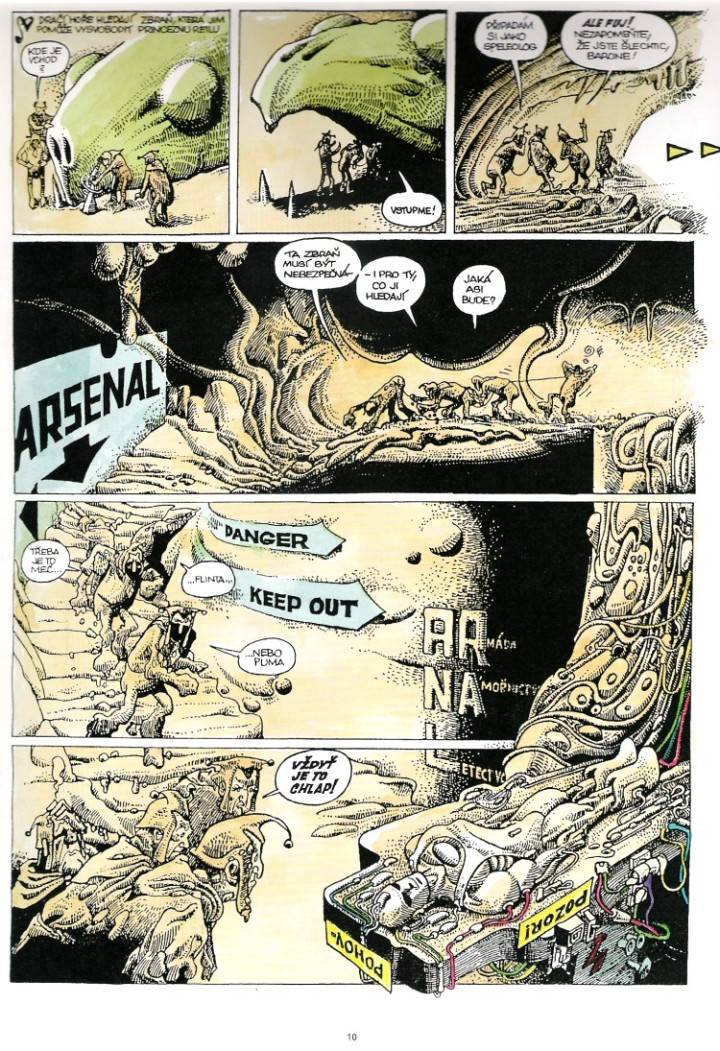

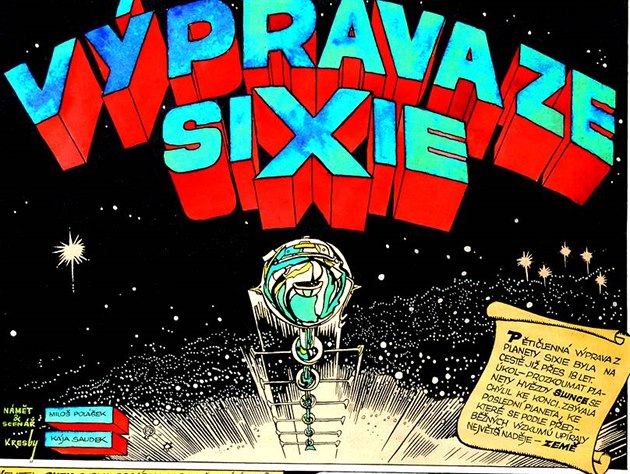

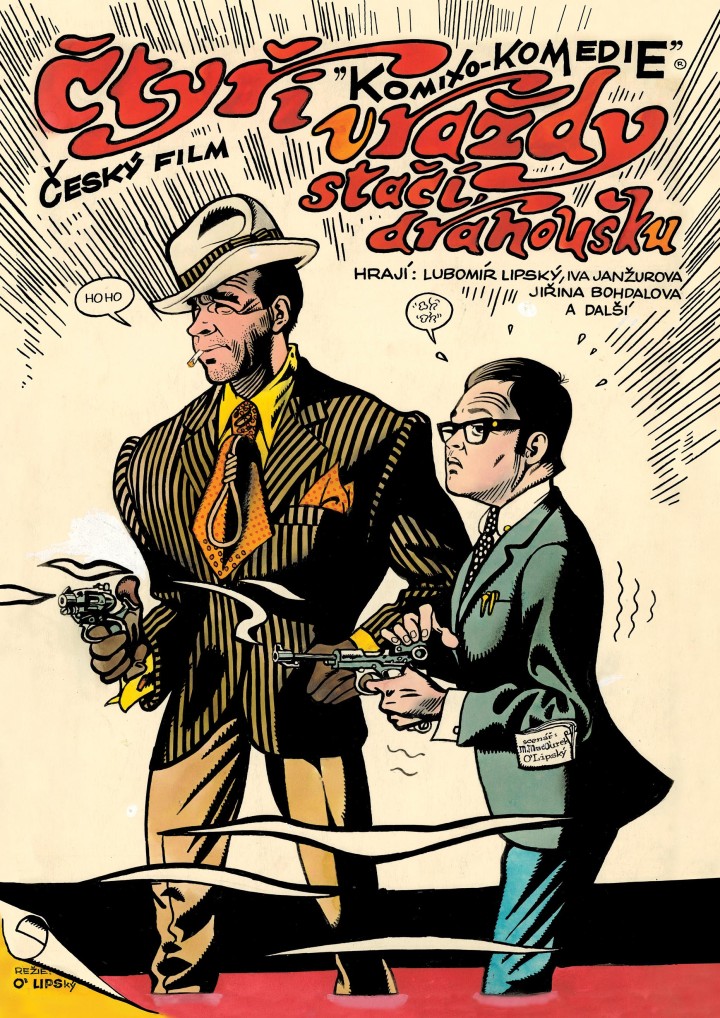

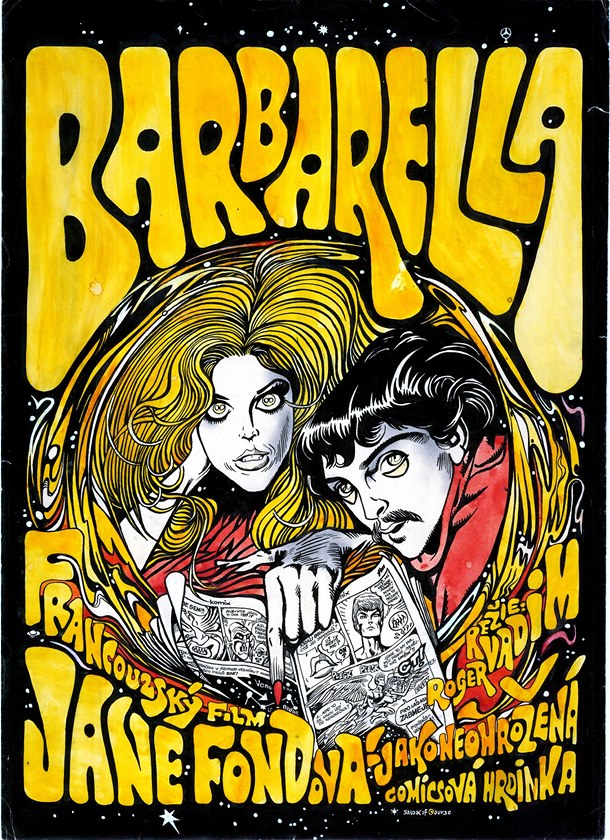

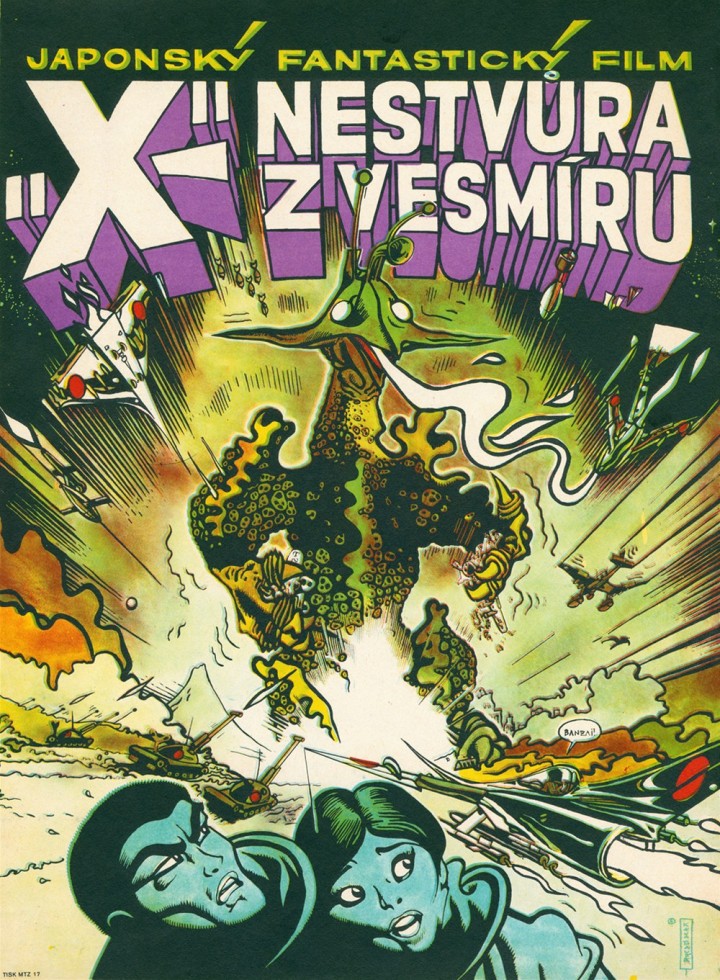

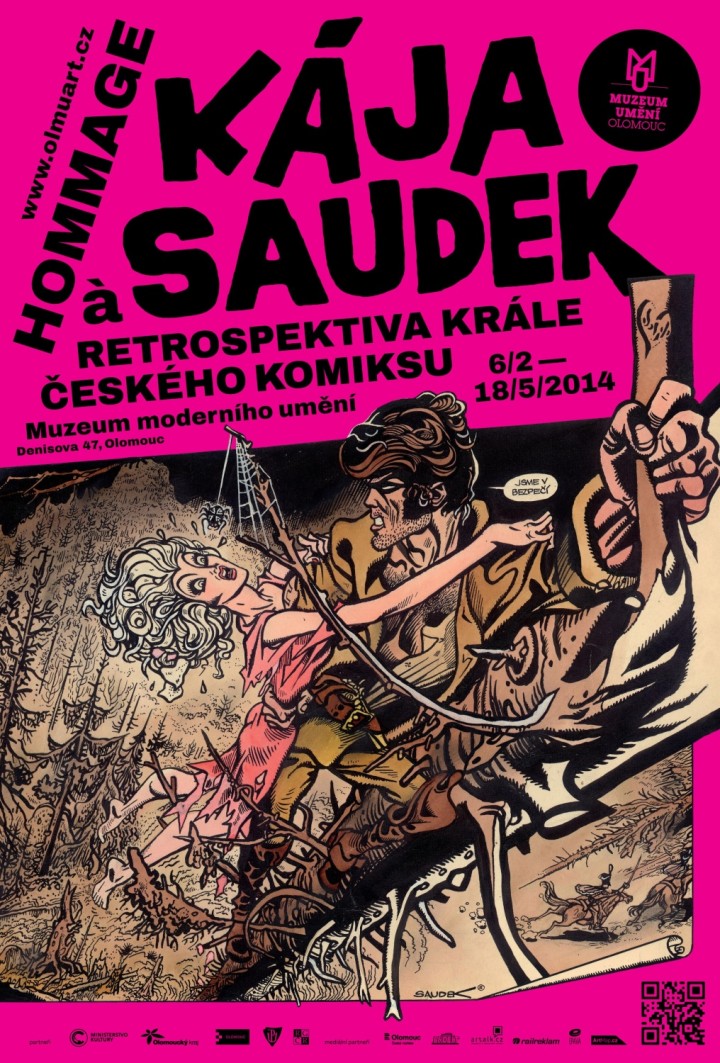

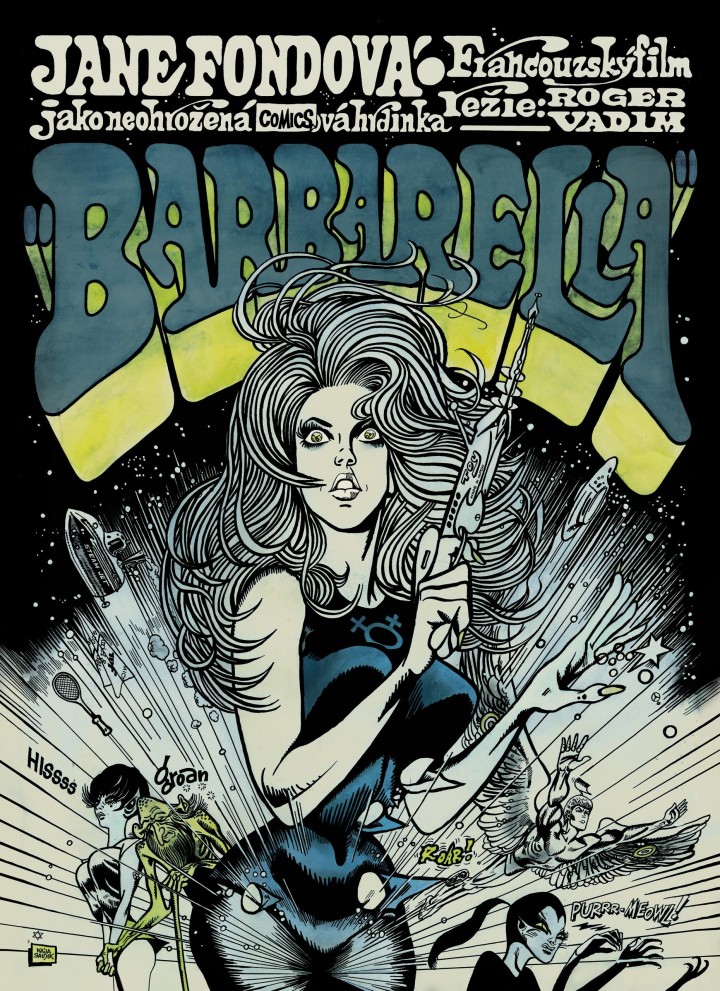

I’ve spent most of the evening looking at the work of Kája Saudek – a Czech artist and designer who worked in comics and created film posters – after being tipped off about him by Markey Funk. Markey had just visited ‘Batalion’, a bar and museum in Prague dedicated to the man and thought I would like the work. He was right, check out all that amazing detail and hand drawn typography – what a find.

I’d seen the Barbarella poster before but never checked on the name, the rest was new to me, a mixture of Rockin’ Jellybean, Robert Williams with shades of Moebius in places. Sadly, upon checking the wikipedia entry it seems that Saudek died the same day that I discovered him after spending nine years in a coma at a hospital in Prague. Art like this can never die though, he left a huge body of work for us all to enjoy.

A Veterans for Peace UK film, directed by Price James, written by Darren Cullen, featuring Matt Berry. A serious message highlighted by a very clever film. Please read the battlefield casualties website.

Out today is ‘Hall of Mirrors’, the third album by 2econd Class Citizen aka Aaron Thomason, another beautiful collection of haunted beats, raps and atmospheres that I’ve been lucky enough to hear develop over the last few years. You can hear echoes of parts of ‘Magpie Music’ – the track we collaborated on – in some of the tracks and if you enjoyed his two previous albums you won’t be disappointed as he’s crafted another winner and advanced his sound another notch.

The album (very limited vinyl, CD & download) is out on The Content Label from California since Aaron’s previous label, Equinox, closed its doors two years ago. You can order all formats here in various bundles as well as a T-shirt and I nearly forgot, there’s a remix from The Herbaliser that closes the album too. I helped with the typography on the front cover and the excellent front cover was created by French surreal-collagist Albane Simon. Here’s a 15 minute taster for the album mixed by Aaron and he also has all sorts of free downloads, re-edits and videos over on his revamped website here.

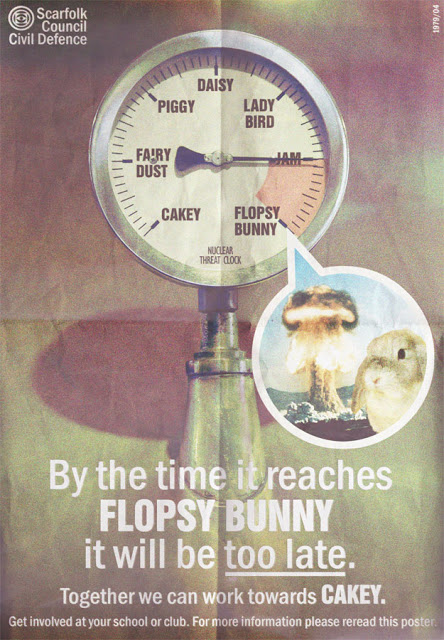

I do love Scarfolk, especially when it’s this random.

I do love Scarfolk, especially when it’s this random.

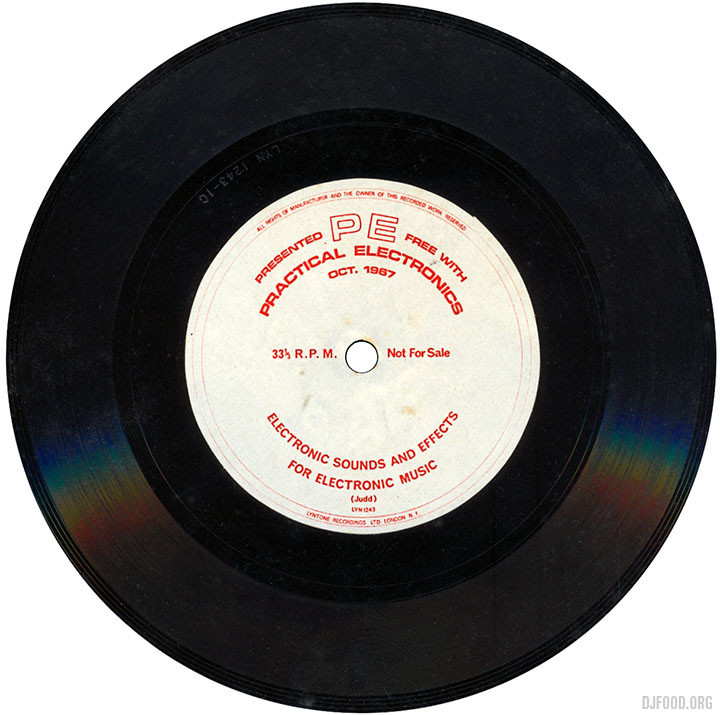

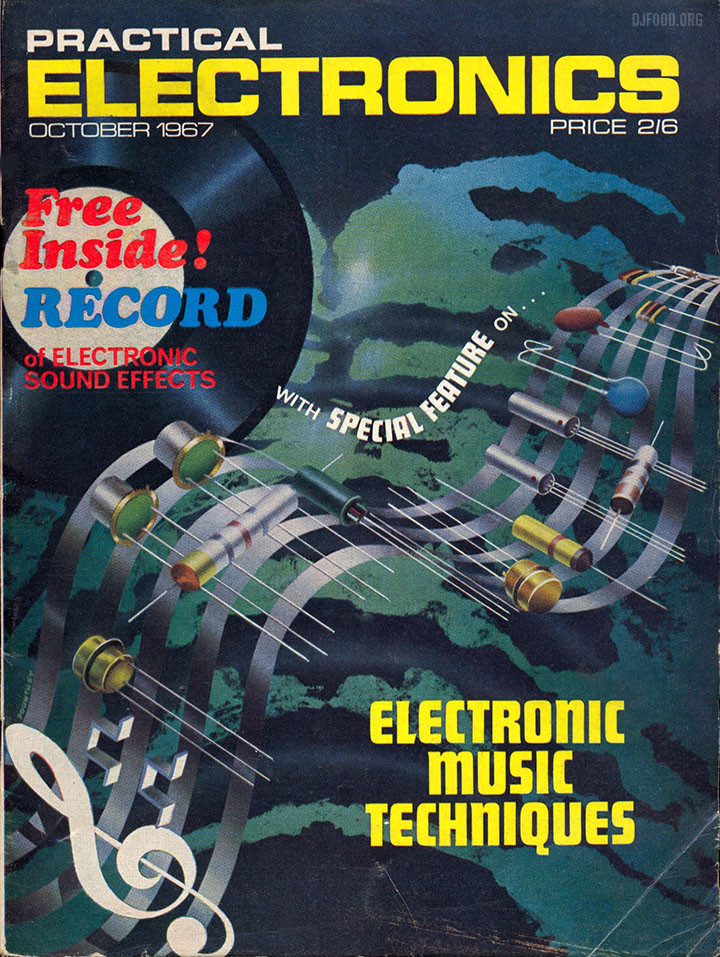

It’s been a while since we’ve had a guest post in the Flexibition and we celebrate the half way mark with Jonny Trunk, someone who should be no stranger to readers of this blog. We start a run of flexi’s given away with magazines with a minor classic of the genre and a treasure trove of sample material, I’ll let Jonny give you the lowdown:

“The Practical Electronics flexi by F.C.Judd (F. C. for Frederick Charles) was only available once, with the magazine’s October 1967 issue. F.C. Judd was a regular writer for PE and other home electronic titles and this comes four years after his own Castle Electronic Music 7” series.

Although issued together, it’s hard to find the magazine and the flexi together these days. If I recall I found the flexi first in an old brown paper bag at Spitalfields market a few years ago. Cost a couple of quid. I found the bag in a box that had come to the market via a North London auction house. The magazine I tracked down a couple of weeks later through a mag dealer. Again a couple of quid.

The PE ‘Electronic Sounds And Effects For Electronic Music‘ record is one-sided and contains a basic introduction to electronic sounds and electronic music generation – all introduced in fairly serious, dry announcements:” (reminiscent of Peter Cook‘s E.L. Whisty character if you ask me – Kev)

Basic Sound Sources

Pure sine wave, square wave, pulse wave from mulitvibrator, Unfiltered white noise

Electronic Treatment

Ring modulated tones, filtered white noise, pulsed tones, attack and decay

Reverberation Effects

Mechanical reverberation, tape echo, excessive echo, pre-echo

Tape Recording Techniques

Replay speed, replay speed doubled, reversed recording, tape loops

Rhythmic Electronic Music

A specially composed short cue for this disc, utlising a melody for which F.C. Judd was awarded first prize in the 1965 British Recording Contest (professional section).

Judd was an early electronics pioneer (still largely unknown next to his Radiophonic Workshop peers) who contributed the music to the British puppet TV show, ‘Space Patrol’ and, as Jonny stated, released several 7″s of electronic music and sound FX on the Castle label. He also wrote several books including, ‘Electronics in Music’, which was reprinted in 2012.

This is pretty interesting, both visually and musically, ‘Orca’ – the first track from Nicolas Godin‘s debut album ‘Contrepoint’, due for release later this year on Because Music. You may recognise Nicolas as being one half of Air and although I’m never going to like that bitcrushed guitar sound there’s a lot going on here that makes me want to hear more.

Download the single here : http://po.st/OrcaSingle

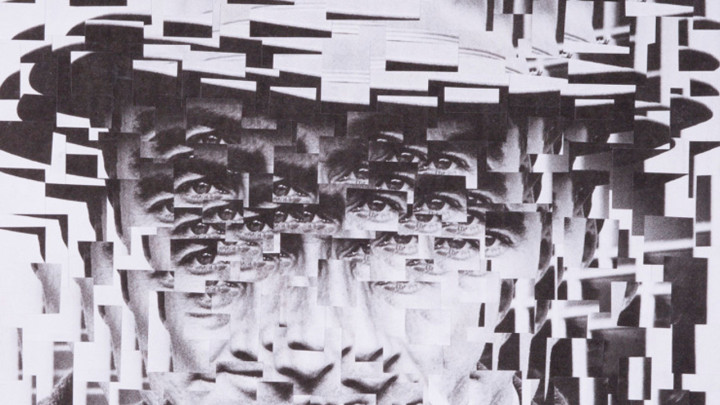

This Thursday sees a half hour documentary about the cut up on Radio 4 at 11.30am narrated by Ken Hollings and featuring, Cassetteboy, Armando Iannucci, Vicki Bennett (People Like Us), Lenka Clayton, William Burroughs‘ biographer Marry Miles, Matt Black and myself talking about the art of the cut up.

Put together by Dan Shepherd at Far Shoreline productions over what feels like two years or more since he first contacted me and picked my brain for content and angles, it deals with the spoken word cut up rather than the musical mash up. Focusing on spoken word (well, this is Radio 4) meant that the programme could narrow its sights and navigate a precise lineage from Burroughs’ literary and spoken cut ups through to today’s practitioners. I can’t give much more away as I’ve not actually heard the finished thing yet but, knowing Dan’s work and love of the medium and with Ken on board I’m confident it will be a great listen.

Ken has written a blog post about the making of the half hour programme here and was fascinating to meet, if you don’t know his writing then it’s quite something and not for the casual reader. The documentary will be online to UK listeners for a month and Dan promises an extended podcast version should be available to all at some point afterwards via his site.

(The top image is unrelated to the doc but illustrates a different kind of cut up perfectly, Lola Dupre‘s Robert Oppenheimer, paper collage – check her amazing collage work here)

PS – Ken has also written a piece for The BBC website giving an introduction to the Cut Up here that’s well worth a read.

Awesome trailer for a forthcoming game about the devil, looks like an old Fleischer Brothers cartoon!

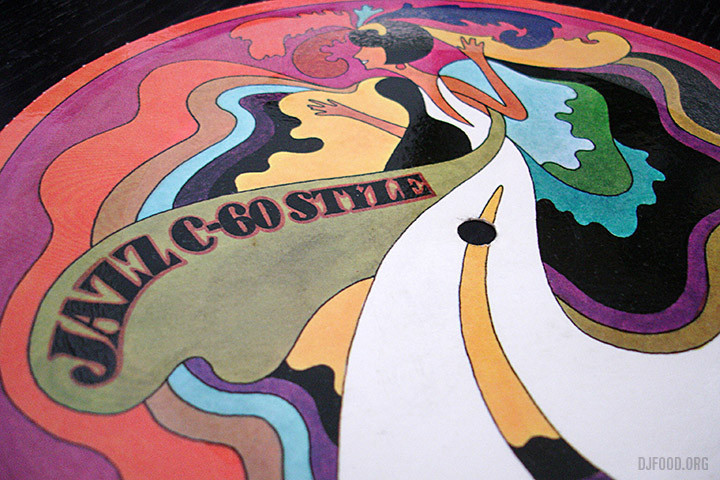

Not so much a flexi but more of a sound card being that the grooves are pressed into cardboard. The sound quality is terrible but it’s all about the graphic here as this was one of the first discs that gave me the idea to do this weekly show and tell. Not much contextual information with this one but the reverse ‘label’ states that the image artist is John Trotta (correct spelling) who did cover illustrations for many classical titles on the Nonesuch label as well as some work for Sesame Street.

He is woefully under-represented on the web it seems, with a style reminiscent of Milton Glaser or Heinz Edelmann. There are also a couple of spelling mistakes on some of the players’ names too, most of them reputable jazz players with many titles under their belts. If anyone can shed any more light on this disc I’d appreciate it.

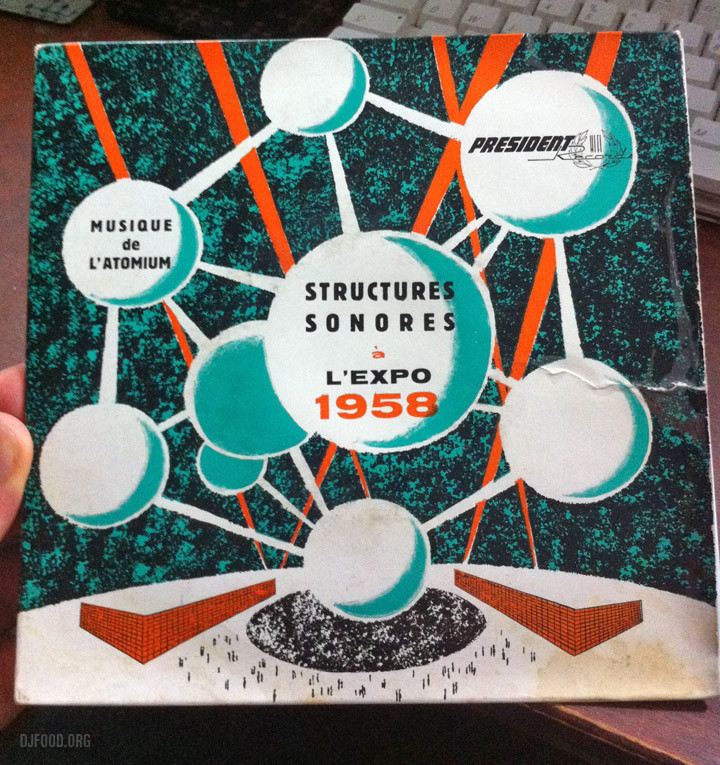

Music de L’atomium, made for Expo ’58, also known as the Brussels World’s Fair. 7″ on President Records with Structures Sonores played by Y. Lasry, F. & B. Baschet, J.P. Cotte and J. Chouet – you can hear one side of this single on the Cacophonic compilation of Lasry / Baschet recordings, ‘Instruments Non-Electronique’

Music de L’atomium, made for Expo ’58, also known as the Brussels World’s Fair. 7″ on President Records with Structures Sonores played by Y. Lasry, F. & B. Baschet, J.P. Cotte and J. Chouet – you can hear one side of this single on the Cacophonic compilation of Lasry / Baschet recordings, ‘Instruments Non-Electronique’

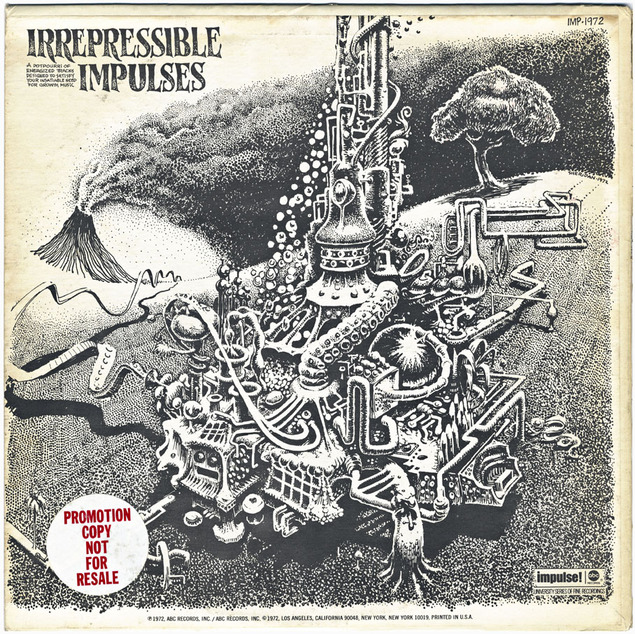

I found this Carl Oglesby album with a cover illustrated by Dave Sheridan, the comic artist who worked on titles like Dealer McDope, The Leather Nun and some of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. Now sadly deceased, Dave’s work is always hyper detailed and tripped out, I featured another of his covers some years back, an Impulse Jazz compilation – I wonder if he ever did any more record sleeves?

I found this Carl Oglesby album with a cover illustrated by Dave Sheridan, the comic artist who worked on titles like Dealer McDope, The Leather Nun and some of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. Now sadly deceased, Dave’s work is always hyper detailed and tripped out, I featured another of his covers some years back, an Impulse Jazz compilation – I wonder if he ever did any more record sleeves?

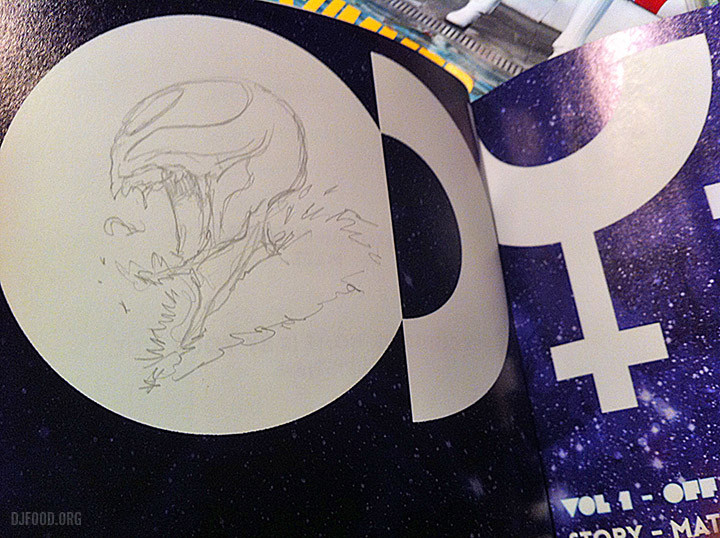

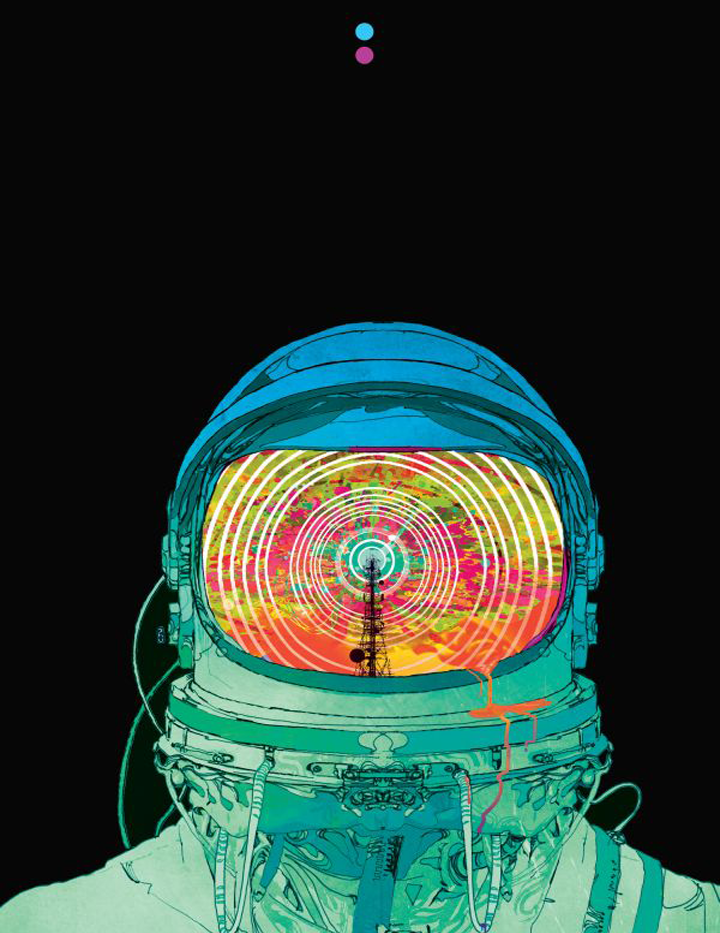

I met Christian Ward last Friday when he signed copies of the new trade paperback of his and Matt Fraction‘s ‘ODY-C’, at Gosh! Comics, an epic psychedelic space take on The Odyssey with the roles reversed. If you like your female leads strong and ruthless, your Gods devious and wrathful and your art cosmic then this is the book for you, a gritty, multi-layered take on a classic with out of this world page layouts and colour.

I met Christian Ward last Friday when he signed copies of the new trade paperback of his and Matt Fraction‘s ‘ODY-C’, at Gosh! Comics, an epic psychedelic space take on The Odyssey with the roles reversed. If you like your female leads strong and ruthless, your Gods devious and wrathful and your art cosmic then this is the book for you, a gritty, multi-layered take on a classic with out of this world page layouts and colour.

(Photo © Gosh! Comics 2015)

He was kind enough to do me a quick Cyclops sketch and Gosh! are selling the lovely Spaceman print above for a very reasonable £20 which looks beautiful framed in my studio.

Balkan Recordings have put together a compilation of tracks from Balkan artists & friends, to raise money & awareness for Nepal called ‘Mountain Electrics‘. It features tracks from: RAIM, Cardopusher, Perseus Traxx, Symmetry, Posthuman, Hrdvsion, Mark Archer, Myth!, White Lodge, Luke Vibert, Room 13, Mark Broom, Shinra, Shadow Dancer, B12, Echaskech, Nightwave, The Village Orchestra, Paul Mac, Chevron, and Warlock who have contributed their tracks for free.

The digital compilation is priced at pay-what-you-choose via their Bandcamp page (all money received via bandcamp will be donated via Just Giving, claiming UK Gift Aid) – you can download and pay, or donate directly at justgiving.com/mountainelectrics. They have chosen CANEPAL as their charity as they have been working in Nepal for years previously to the earthquakes and have staff on the ground & long-standing local knowledge and ties. Their operations & staff costs are funded by other means, meaning 100% of donations go to their work in Nepal. For more information check their site here: http://www.canepal.org.uk

The digital compilation is priced at pay-what-you-choose via their Bandcamp page (all money received via bandcamp will be donated via Just Giving, claiming UK Gift Aid) – you can download and pay, or donate directly at justgiving.com/mountainelectrics. They have chosen CANEPAL as their charity as they have been working in Nepal for years previously to the earthquakes and have staff on the ground & long-standing local knowledge and ties. Their operations & staff costs are funded by other means, meaning 100% of donations go to their work in Nepal. For more information check their site here: http://www.canepal.org.uk

Along with the forthcoming Episode 7 trailers and Star Wars Secret Cinema, these Battlefront trailers really are making me fall in love with the Star Wars universe all over again after years of not caring after Lucas’ terrible second trilogy. All three recapture the thrill of the original films like nothing since the 80s.

The Gamma Proforma label is on fire this year with the Divine Styler album, a new T-shirt series featuring Augustine Kofie and Will Barras plus retrospective books of Will’s work as well as graphic design legend Ian ‘Swifty’ Swift. Not only that, their ‘Cosmic Flush’ series of 12″s and prints based on The Rammellzee‘s last work now reaches it’s third installment. Delta is on the art and Mike Ladd on the remix and I’m starting to suspect Rob Swain from Gamma is mining some telepathic mind link with me as all the releases so far push all the right buttons for me. Pre-order the third part, ‘Crayzay’, here.

The Gamma Proforma label is on fire this year with the Divine Styler album, a new T-shirt series featuring Augustine Kofie and Will Barras plus retrospective books of Will’s work as well as graphic design legend Ian ‘Swifty’ Swift. Not only that, their ‘Cosmic Flush’ series of 12″s and prints based on The Rammellzee‘s last work now reaches it’s third installment. Delta is on the art and Mike Ladd on the remix and I’m starting to suspect Rob Swain from Gamma is mining some telepathic mind link with me as all the releases so far push all the right buttons for me. Pre-order the third part, ‘Crayzay’, here.

If you’re lucky there may still be some copies of the first and second releases with prints by Futura and Ian Kuali’i with remixes by Divine Styler which will form part of the full box set to the ‘Cosmic Flush’ album release. Check out Will’s Rammellzee graphic for the second T-shirt in the X99 series below too, in fact check out the whole site as there are loads of free mp3s, plus a selection of books, magazines, prints and T-shirts, they even have Syd Mead designs!. Gamma’s shaping up to be the label to watch in 2015.

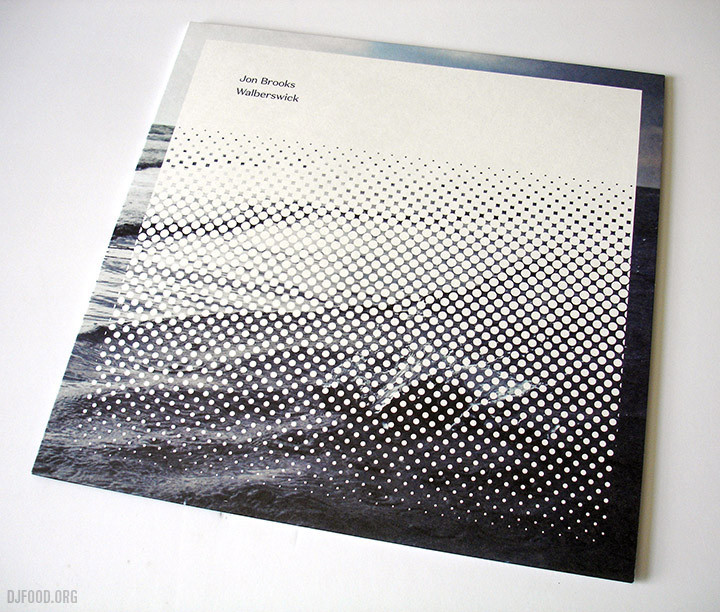

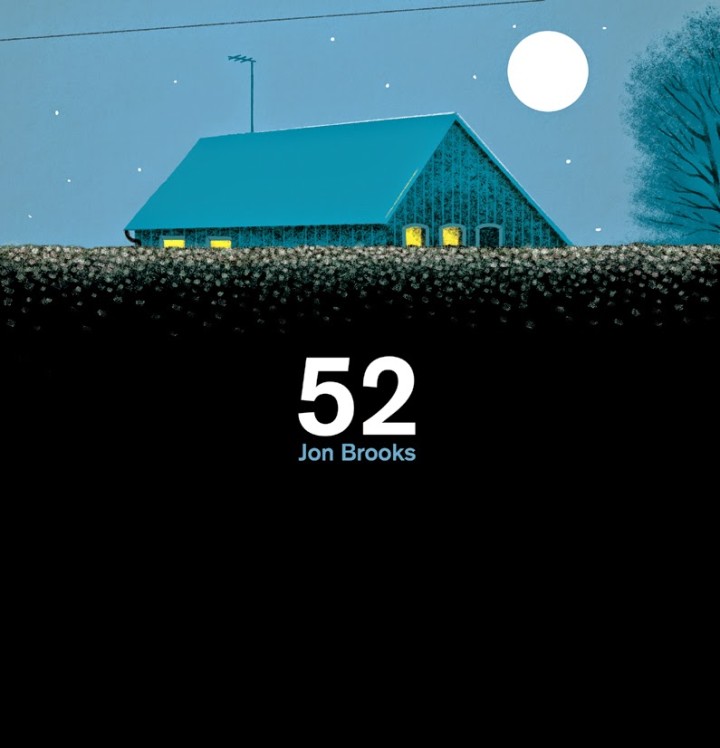

Not content with issuing his ‘MuSIC FOR THOMAS CARNACKI’ album from his own Café Kaput label on vinyl earlier this year, Jon Brooks albums are cascading out of the woodwork this year. His latest, ‘Walberswick’, on Canada’s More Than Human Records is sold out on vinyl and two more reissues are about to hit the shops. His ’52’ album for Clay Pipe Music gets an ‘evening edition’ repress at the end of June with a new version of the sleeve picturing the house during the twilight hour, a clever way of presenting a second run. Pre-order here – be quick!

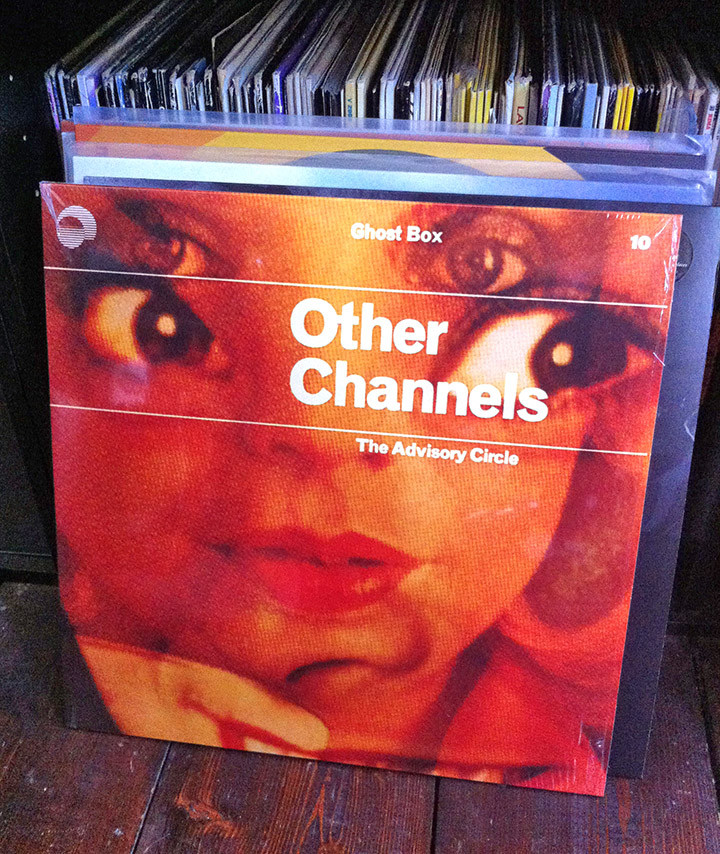

The last album from his Ghost Box discography to get the vinyl treatment also arrived last week with 2008’s ‘Other Channels’ under his The Advisory Circle alias, Brooks at possibly his most ‘hauntological’, it’s a favourite. Another of the GB back catalogue getting a vinyl outing for the first time is ‘The Seance At Hobs Lane’ by Mount Vernon Arts Lab, their sole release so far on the label and itself a reissue from 2001. Order them both here (free download only with GB shop orders too!)

This is interesting, Blade Runner as you’ve kind of seen it before but not quite. I’m unsure where the Harrison Ford dialogue originates from (I don’t remember that much in the first cut) and if you’re not a fan of the narrated original then stop right here as it drives this cut and glues the shots together. But love it or hate it, it fleshes out the story that we all know in unexpected ways (Deckard‘s broken relationship for instance) but it gives away a little too much and Scott was ultimately right to drop it.

There’s certainly material in here that I’ve not seen before and I’ve seen and read a fair bit about the film, the soundtrack as well, there’s different material in here from that too. A scene with Gaff and Bryant that expands on the former’s role in the film is a revelation and, aside from the odd clumsy cut, it offers an new view on what the film could have been, and it’s full of clichés as a result. A couple of key scenes use dialogue to fill the gaps, the death of Zora and Tyrell are both dealt with in seconds and offer a powerful alternative to the graphic endings they come to in the film, showing via implication rather than as we know them.

The biggest omission is the whole end section with Batty before his big scene and the original ‘happy’ ending gets even more footage which changes the tone. Several lines later omitted possibly play on the ‘is Deckard a Replicant?’ mythos, Rachel proclaiming, “we were made for each other”, which to my mind is a genius line. All in all it’s a fascinating 45 minute look at what could have been and testament to the enduring power of the original that people keep on exploring its hidden depths.

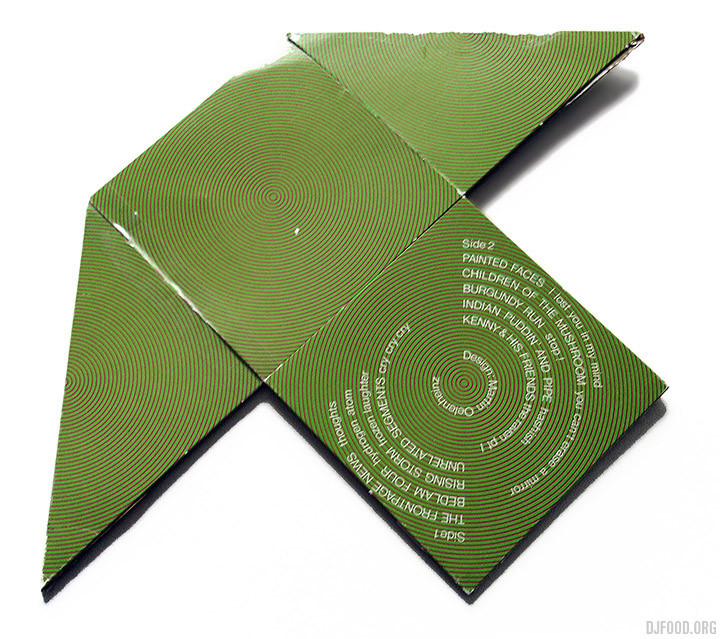

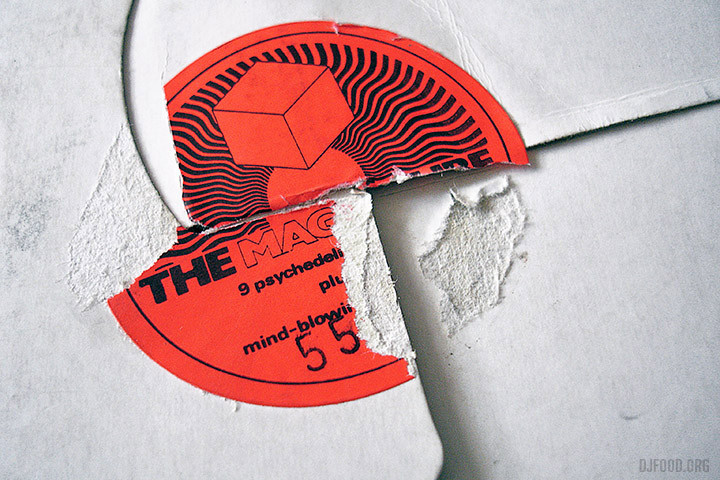

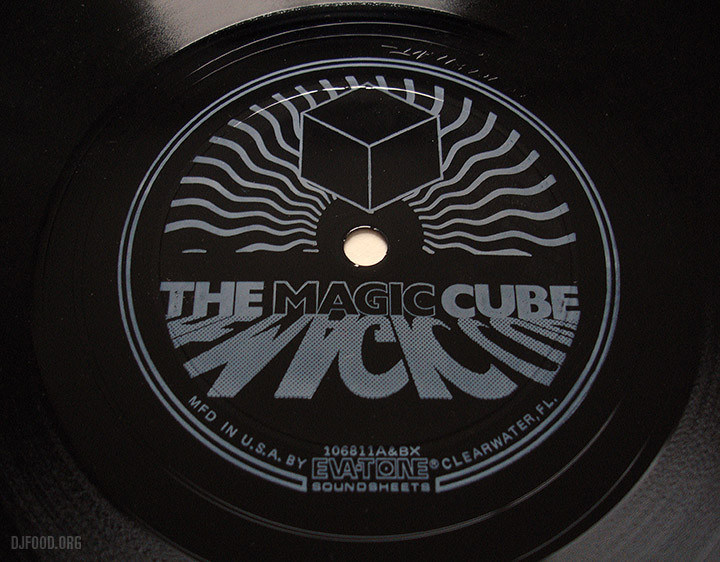

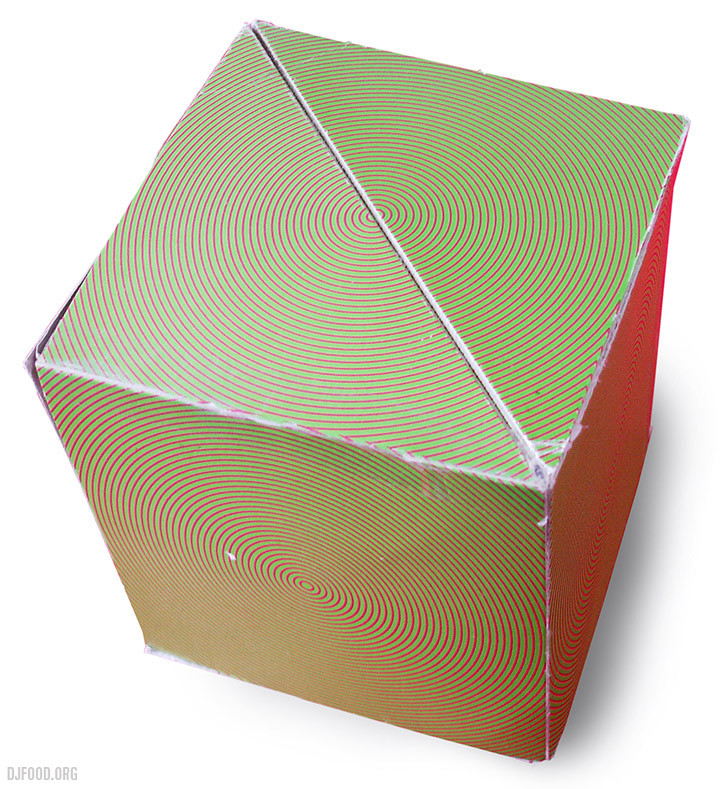

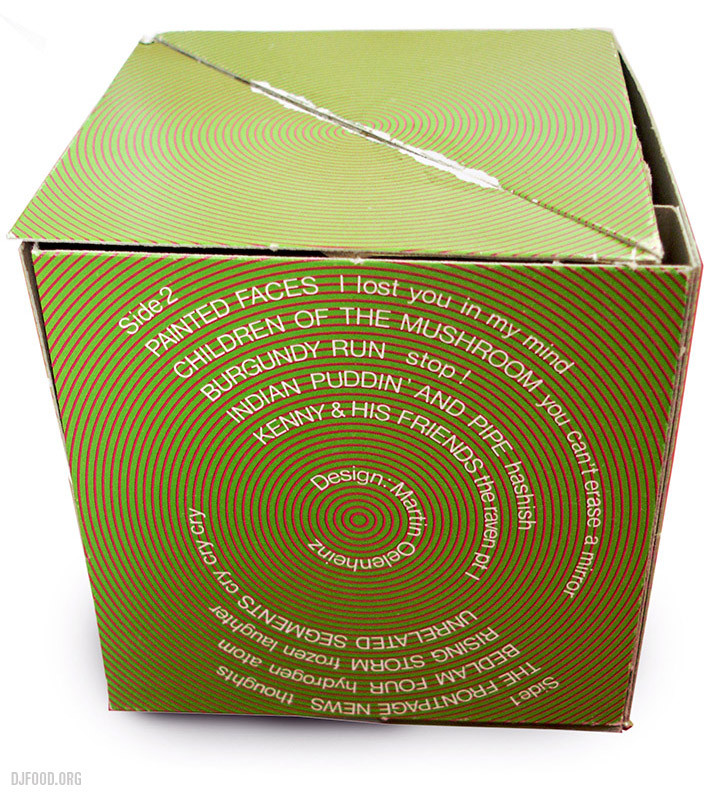

The Magic Cube is a real oddity – a 9″ flexi disc that comes in a stickered envelope with a flat-packed cardboard cube that springs into shape once opened. Or that’s the idea, you have to attach a fiddly elastic band inside the cube for it to work and even then it’s slightly haphazard in shape, leaving you wondering, ‘why?’. It’s a clever bit of paper engineering but its only purpose seems to be to carry the track list for the disc it arrived with (it’s too small to fit the flexi inside).

Designed by Martin Oelenheinz and released in 1982 with a sticker stating ‘9 Psychedelic Greats plus Mind-Blowing Gimmick’ and a hand stamped number for the edition (mine is a bit worse for wear). There’s virtually no info about it on the web and the only label info is Eva-Tone. The music contained on the double-sided disc is full on fuzzed out 60s garage and psych rock as you can probably tell by the titles above. Most of the tracks are on YouTube and it’s all pretty great stuff. Anyone with any more info please post in the comments, I’d like to know where this was first available and who / why / what the thinking was behind it.