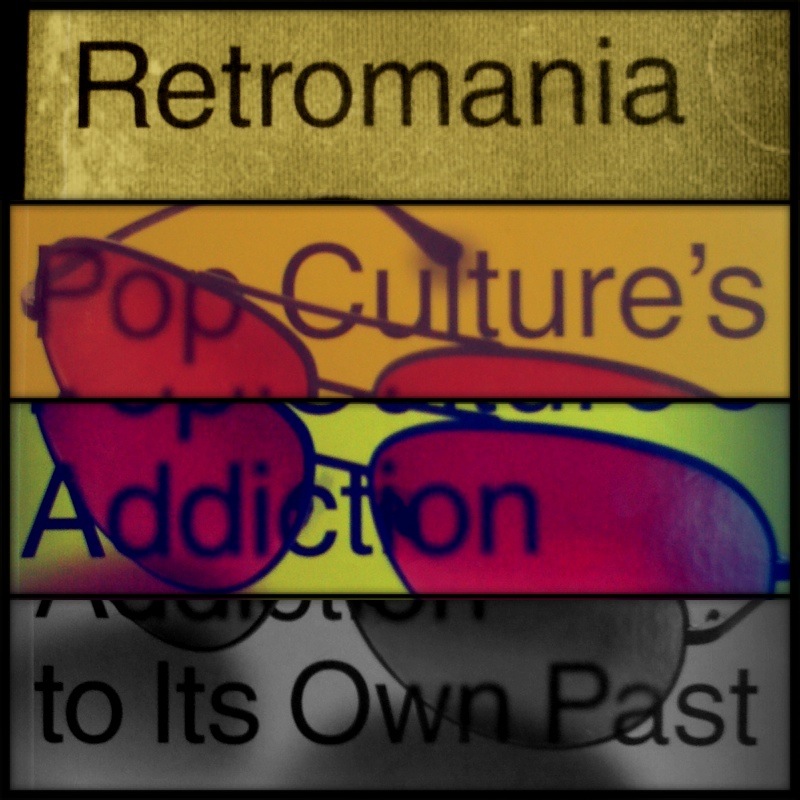

I’ve just finished reading this and regular readers of this blog will have seen me waxing lyrical over Reynolds‘ writing in the past. His latest is a timely examination of our obsession (or is it his obsession?) with the past in current culture with particular focus on the saturation of retro over the last decade. In short he believes we are currently more obsessed with the past than the future, especially in music but the same things permeate other strands of media too, film for instance. It’s an excellent, well researched and thought-provoking work, which I would currently hold up as my book of the year so far. He weaves many different strands from all areas of culture together, sometimes to his own convenience, missing out conflicting examples that weaken his own theories, but, for the most part, he’s spot on in his analysis.

I’ve just finished reading this and regular readers of this blog will have seen me waxing lyrical over Reynolds‘ writing in the past. His latest is a timely examination of our obsession (or is it his obsession?) with the past in current culture with particular focus on the saturation of retro over the last decade. In short he believes we are currently more obsessed with the past than the future, especially in music but the same things permeate other strands of media too, film for instance. It’s an excellent, well researched and thought-provoking work, which I would currently hold up as my book of the year so far. He weaves many different strands from all areas of culture together, sometimes to his own convenience, missing out conflicting examples that weaken his own theories, but, for the most part, he’s spot on in his analysis.

The book touches on so many things I’ve felt over the past few years although I’m in a slightly different camp to Simon on whether this is a good or bad thing. His stance is that music has always been forward-looking and progressive, this has largely stopped during the noughties with revivals and remakes taking more and more precedence over originality and innovation. I don’t think we can help but look back now that there is so much music history and we have the tools to access it, it’s human nature to reminisce. Being a collector through and through, part of my interests lie in the past as much as the present so I am constantly referring back and have found more to love in sounds and visuals from the past than the present over the last decade.

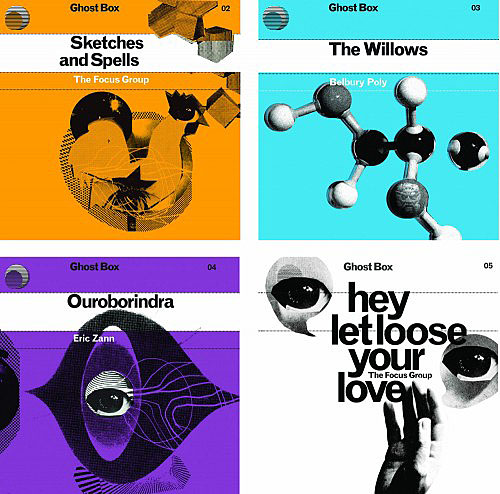

I’ve increasingly found that the things I’m attracted to and am moved by, look and sound ‘old’ for want of a better word, actually ‘analogue’ rather than ‘digital’ would be a better description. I’d say at least half the music I buy is either more than two decades old, whether it be original pressings of vintage vinyl or ‘new’ reissues on labels like Trunk, Finder’s Keepers or Now Again. Of the new music I like, a lot of it uses a dated sound palette, either through samples, analogue gear or styles that glance back to a bygone era, then makes something new from it rather than constantly forging ahead into uncharted waters. Labels like Ghost Box and bands like Boards of Canada (both given a hefty space in ‘Retromania’), Amorphous Androgynous and Moon Wiring Club all come infused with a sense of the past, recontextualised into the present. Hip Hop has largely changed so much in the last decade it’s unrecognisable to the original aesthetic but labels like Stones Throw and artists like Edan, Cut Chemist, Sound Sci and DJ Format still produce work that carries the torch from the golden eras for those who don’t want bling, bitches, Crunk or Hyphy. Sonically, the fashion for compression, brick wall limiting and side chaining in production over the last decade – the so-called ‘Sound Wars’ – does little for me besides make it increasingly harder to play older tracks alongside new ones in a DJ set or mix without having to ramp up the EQ and gain.

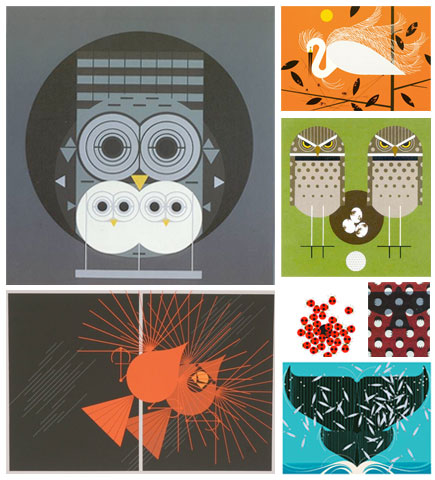

Visually I’ve also noticed similar patterns in graphics and illustration: Julian House‘s roughly cut collage style, aping the Penguin book design aesthetic of yesteryear, Jeff Jank‘s work for Stones Throw, the return of screen printing on record sleeves, the kind of illustrators featured on sites like Grain Edit, wildly riffing off the textures and colour palettes of Charley Harper. Witness iPhone photo apps like Hipstamatic, Leme Leme, Tiltshift Generator introducing abnormalities and grit into images (my own efforts with Simon’s book, above) and Ashley Wood’s 3A toy company artificially ‘weathering’ their figures. Texture and grain, both in sound and vision, are part of the package for me, give me that over florescent colours, CGI or auto-tuned gloss any day. I guess my tastes are out of step with what’s deemed ‘current’ but I’m obviously not alone as there is plenty of material out there referring to bygone days for inspiration without soullessly copying.

This is where I think Reynolds falls down slightly, towards the end of the book he makes a couple of wild generalisations that just don’t hold up for me. Saying, “Nothing on the game-changing scale of rap or rave came through in the 2000s”, is a bold, sweeping statement and plenty of new styles of music emerged in the noughties. Both new and retro appeared, some being micro genres of existing styles, some, make overs of older ones. Aside from the Bastard Pop /Mash up craze – which was unashamedly retro and, I think, more a response to the turn of the century than anything else, you had: Hip Pop (my phrase) the Neptunes/Timbaland years of credible Hip Hop and Pop, Dirty South / Crunk / Hyphy, Minimal Techno, Dubstep (the big new one), Baile Funk, Funky, Grime, Juke/Footwork/Kwaito, Hauntology, Wonky, Electroclash (fairly retro), and the resurgence of Rock, Folk and Psychedelia (very retro) … and they’re just the ones I can think of off the top of my head.

Reynolds is right in the respect that there’s nothing there that swept into our lives and changed everything overnight and a lot of the above are variations on existing genres. But he’s also writing from the perspective of a man in his late 40’s who’s lived in the US for over a decade. By the time I hit 35 I could see things coming round for a second time, I could pinpoint influences, samples and the like because I’d experienced them the first time round. When I was in my teens, Hip Hop was brand new, including all the samples, some of which were less than a decade old by the time they were sampled (Planet Rock > Trans Europe Express). Someone 15 years my senior would have probably heard what I was listening to and commented that they were just rehashing funk, disco and later, jazz. I doubt many over the age of 30 will feel the thrill and rush of those initial discoveries, those special ones in your teens where you ‘claim’ a music, group or movement as your own.

But to some teenager living in a UK inner city Grime and Dubstep must be/have been their Hip Hop and we won’t know this for another decade or more as it infiltrates the pop mainstream as it’s already begun to. Hip Hip didn’t blow up big for a good 10 years from its inception save for an initial ‘fad’ which the media jumped on then dropped for the next thing. The trouble with the pace of everyday living now is that every little musical movement is examined, dissected, proclaimed dead and then filed away under a new sub-genre heading before it’s even given a chance to evolve. Reynolds is as guilty of this as any current writer, constantly looking for The Shock of the New, that’s part of his job, but I’m not sure if he’s going to find it in quite the same way as rock and rave hit him at a younger age.

The web has unlocked so many secrets that made music and its practitioners appealing and revelatory, even as far back as the 90’s, so much of the mystery of music is gone now as we all scramble to record ever detail of everything we do. Where I had to learn how to scratch by working out the fader movements of DJs by listening to the records you can now watch instructional videos. When I had to search through piles of junk and pick up info by word of mouth on breaks, labels and artists, they’re a quick search and a couple of clicks away now. Obscure films glimpsed on late night TV or on short film festival line ups can be found easily. But none of this is a bad thing, and I’d never want to go back, returning to collector/seeker mode, technology has enabled us to time travel in some respects. The shuffle mode on the iPod can transport us back decades in a single click and the search engine can instantly access more media than we can consume. In that respect, if what’s contemporary isn’t doing it for me then give me the Shock of the Old and I’ll be just fine.

I’ve ended here on a bit of a negative tangent, go and read the book and decide for yourself, it’s an excellent piece of work and I’d hold it up there with David Toop‘s ‘Ocean of Sound’, Paul Morley‘s ‘Words & Music’ and Reynolds’ own ‘Rip it Up & Start Again’.

I think that as critical media fragments so too does the notion of what is and is not culturally important (at least on an artist by artist basis). I think that print, tv and radio have long been the gatekeepers of popular music. Academic music relies more on its own institutions to determine its landmarks. It’s funny to consider that in the time of Chopin, Beethoven was considered old-fashioned and boring! Within a few years of Chopin’s death his music attracted the same criticism. I think that the wave of fashion ripples and flattens over-time, it’s best to take the long view.

So, without going too far off topic, I have no idea what will and will not be remembered by people, I guess the important thing is just to maintain your own curiosity and passion and let everything else flow. Of course, when you’re talking about a commercial release that has to pay for itself the anxiety takes on a slightly different light. You’re definitely right though – it’s futile to try to please people. I’d rather listen to a re-imagining of the past than a pastiche of the future

I’d love it if all comments were as incisive as this and congratulations for the longest comment on my site by a long stretch. You’re right on the technology of course, we wouldn’t have acid without the 303 etc.

I could probably write an essay on this but wanted to keep it as brief as possible, I too think about this sort of thing a lot and have increasingly felt out of step with what’s currently deemed hip and fashionable. Not that I’m particularly bothered by that because I think things go in waves and we zigzag in and out of contemporary scenes all our lives. It’s just a little frustrating when you’re about to release a record that’s not in tune with the zeitgeist. My way of looking at it is that the record you make should be able to stand up over time rather than try to shoehorn itself into what’s ‘hot, you’ll only date all the quicker that way. The trouble is that the record label still has to promote and sell something in the current marketplace but I’d rather a record sell steadily and stay on catalogue than be a flash in the pan. I wonder how many ‘classic’ albums we’ll have in 20 years time from the last decade.

Great post.

It makes you realise how sensitive we are to medium. Even non-musical people have the ability to quite strongly associate a recording to a time and place, allowing them to expand on that universe, evoking so much more than a ‘perfect’ recording might. I’d much rather listen to a blues song recorded in the 1930’s than even one recorded by the same artist in the 50’s or 60’s. The noise sparks my imagination. Without wanting to gush it was always what endeared me most to the Kaleidoscope album – it had a real sense of time and place, but it was not our own. To my ears it felt like the audio equivalent of an alternate history.

I think it’s also important not to under-estimate the influence of technology on musical trends. The most significant (or at least the most pervasive) developments in audio over the past decade pertain to playback, reproduction and emulation. Often a new branch in music requires a single piece of disruptive technology (or in the case of punk, a disruptive culture). When Reynold’s states the impact of hip-hop and rave does he mention that both were driven in large-part by the respective technologies of turntables, samplers, drum-machines and so forth? The past decade has seen huge increases in CPU and available music software, lo-and-behold much of the music that has established itself takes advantage of this. I can’t imagine trying to write a dub-step tune on old hardware samplers. That’s not to say it isn’t possible, but the creative leap required to consider doing so would have been that much larger. These days you can just stack a couple instances of Massive, dial-up some presets and off you go (*shudder*).

One of the effects of the always-on culture is that it doesn’t allow for isolation in quite the same way as it used to. Maverick composers generally enter from outside the field, having worked for years in comparative isolation their advances are as much a result of naivety or eccentricity as they are intention. Alternatively they are a part of a scene (or school) and their innovation is driven by healthy competition. The internet leans much more heavily towards this second group, where people are exposed to far more music and are able to get feedback from others much more easily. This causes people to tend more towards evolutionary creativity rather than the big genre defining leaps.

Sorry for the mini-essay. I often find myself thinking about this stuff. Again, great post, I might have to get hold of this book…